A Doctrine Analytical Philosophers Love To Hate

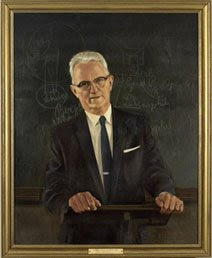

As I have begun reading the new edition of Cornelius Van Til’s The Defense of the Faith I was reminded that he affirms a doctrine many people in our day love to hate. No, I am not talking about predestination. Nor am I talking about the antithesis. I am not even talking about the controversial doctrine of common grace. Rather, I am referring to the doctrine of divine simplicity (31). This is a doctrine disliked especially by a cadre of analytical philosophers, among them, the prince of Christian philosophers Alvin Plantinga. He, of course, is not alone in his rejection of divine simplicity. It tends to go the way of the dodo bird with social Trinitarians, feminists, other egalitarians, and open theists as well.

This is not the place to go into the exquisite niceties of analytical philosophy. My concern is point out that the doctrine plays a significant role in the theology and apologetics of Van Til. Admittedly it stays in the background most of the time and some might want to refer to it as the “great assumption.”

By now you may be wondering, what is this doctrine of divine simplicity all about anyway? It is the doctrine that derives from the fact that God is a spirit and has no parts. That is, God is not a composite being in the sense that he is made up of pre-existing parts or attributes or characteristics. He cannot gain any new parts nor can he lose any. With relation to time we might say there is no before or after with God as he is in himself. And spatially there is no here or there.

In case you are beginning to think this all sounds rather abstract and obscure, here is the cash value of the doctrine. If God is not simple, that he means he is derived from parts. That also means that he is dependent on parts. That means he cannot be a se or from himself. You may still think this is heady stuff and that my head is stuck in the stratosphere. But if God is not simple that means he cannot be the self-contained ontological Trinity that Van Til is always affirming. What’s more. His knowledge and his being would not be coterminous. Another truth Van Til would like to consistently and constantly affirm. And if his being and knowledge are not coterminous, that means that God has something to learn. There is something that he does not know. He can no longer know himself nor his creation exhaustively.

And by the way, there is a biblical basis for divine aseity and simplicity and that can be found in Exodus 3:13-15. There we see the independent God explain to Moses just who he is,

Then Moses said to God, “If I come to the people of Israel and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I AM WHO I AM.” And he said, “Say this to the people of Israel, ‘I AM has sent me to you.’ ” God also said to Moses, “Say this to the people of Israel, ‘The Lord, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you.’ This is my name forever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations.

God is who he is, “I am who I am.” It is this God, whom we later learn, as revelation progressively unfolds, is one being in three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. God is not dependent on you or me and he is holy and high above his creation. And yet this very Triune God has entered into contact with his creation.

The great temptation is to assume that for God to interact with time and space-bound finite creatures that he must not be what Christianity has classically claimed he is. Among other things he is simple. He is not made up of parts that exist before him or that will remain long after he is gone (whatever that may mean).

It really is as simple as that!

Jeff,

Could you elaborate (in a somewhat basic way) why it is that the doctrine of simplicity has received so much flak from theologians such as Plantinga. When you define it the way that you have then I ask myself “that sounds quite obvious!”, but then for some like Plantinga it obviously isn’t! I just want to know what their concern is.

Does that make sense?

Mike

Mike

It is a very technical discussion and I am still wrestling with understanding all the ins and outs of it. But you can find a discussion by Plantinga in his “Does God Have A Nature?” Here Plantinga denies that God is his nature, but that he has one. One assessment can be found here: http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/papers/dghn.htm.

Thanks for the link.

Very good post and comment response! And thanks also to Micheal for this very good question. I will also look at Fredosso’s review of Plantinga’s book, “Does God Have a Nature?”

Rob