“Textual, Expository, Redemptive-Historical, Applicatory” Preaching?

Let’s be honest. None of us has the handle on preaching and no two ministers preach the same. John Chrysostym, Augustine of Hippo, John Calvin, Jonathan Edwards, Samuel Davies, Charles Spurgeon, George Whitefield, John Wesley, Archibald Alexander, Martyn Lloyd-Jones and James Boice were some of the model preachers in the history of the church and they all had unique approaches to expounding God’s word and unique personalities that God worked through. Of those living today Sinclair Ferguson, Eric Alexander, Derek Thomas, William Still, John Piper, Edward Donnelly, Ligon Duncan, Ian Hamilton, Phil Ryken, Rick Phillips, Joseph Pipa, Tim Keller, Joel Beeke, Kent Hughes, D. A. Carson, Mark Dever, John MacArthur, R.C. Sproul, Alistair Begg, and Brian Chapell are some of more well known expository preachers–and yet, as was true of those in the history of the church, each one has a unique personality and approach to sermon structure and content.

Some preachers are more textual than others. Some are more topical. Some are more experiential. Some are more exegetical. Some are more explicitly systematic. Some are more explicitly biblical-theological. Some are more culturally engaging. Some are more passionate. Some are more pastoral. Some are more humorous. Some are more somber. Some are more conversational. Some have more heat than others. Some are more didactic. Some are more creative. Yet all of those mentioned above would consider themselves “expository” preachers due to their commitment to preaching in a lectio continua approach. Hughes Oliphant Old has done a great service by illustrating and emphasizing the differences and nuances that exist throughout the history of the church in his seven volume, The Reading and Preaching of Scripture in the Worship of the Christian Church.

So the question we now have to answer is, “If all expository preachers differ in their style, structure and approach to preaching can we say that there is one specific way of preaching that we ought to be aiming for?” The answer is–at one and the same time–‘yes’ and ‘no.’

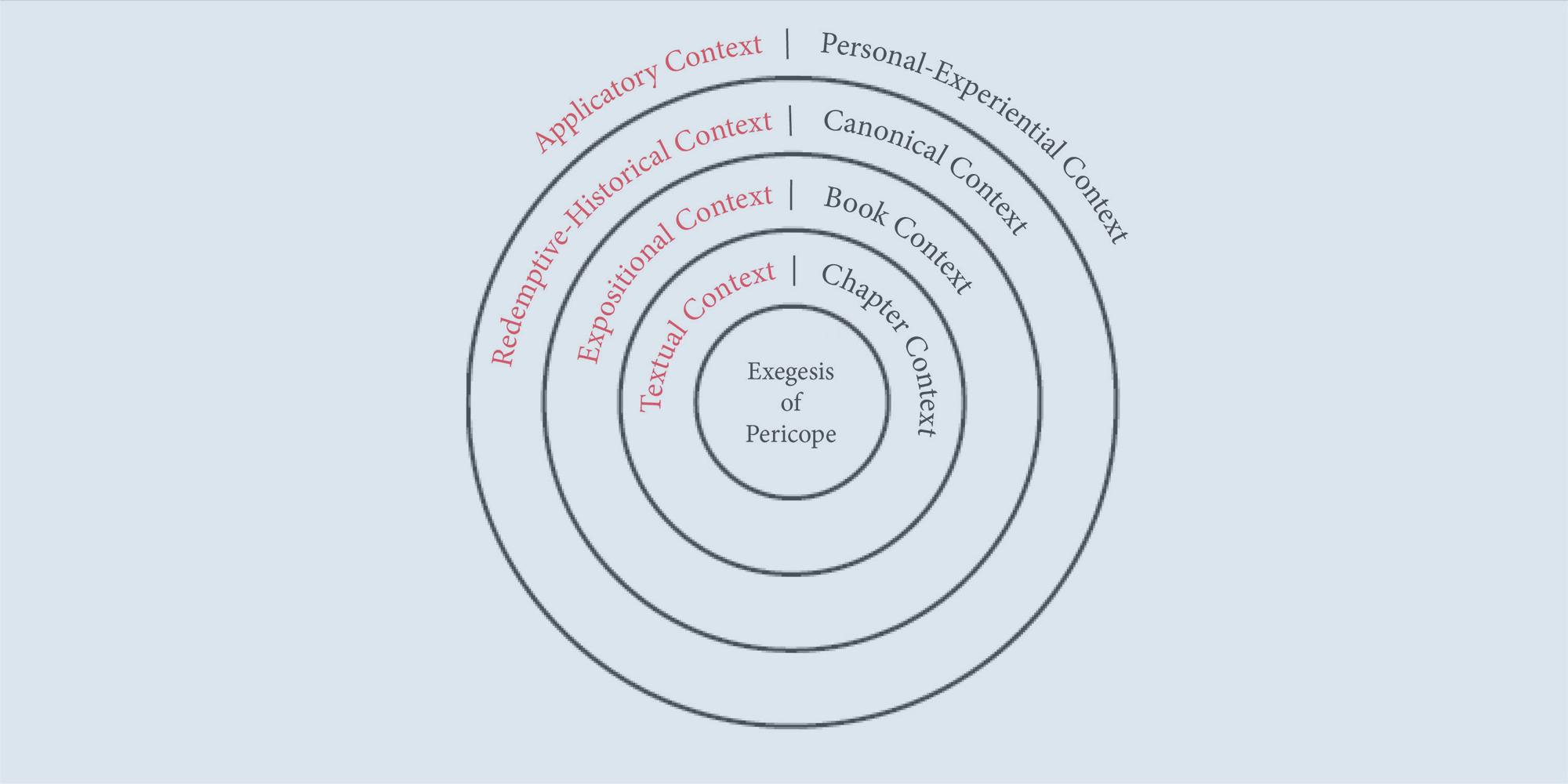

I’d suggest that while there is freedom to differ in many of the categories listed above–and since the Scriptures do not give us a specific homiletical method–we don’t have to press one example as THE example of faithful preaching. That being said, it does seem to me that a “textual, expository, redemptive-historical and applicatory” approach most faithfully takes consideration of the more narrow and more broad context of the message of Scripture and the bearing it has on those to whom it is preached. What do each of these categories mean and how should be go about striving to incorporating them into our preaching of the word of God? The following chart might help us envisage the way in which each text (i.e. the smallest preaching unit or ‘pericope’) has a larger context in the chapter, the book, and the entire story of redemption in Scripture. From there it reaches out into the experience of believers in the world through it’s contextual applications:

Grammatical-Historical-Theological

Before anything can be said about the four contexts that need to be considered in the sermon, brief consideration must first be given to our hermeneutical principles. Once the pericope is chosen, the minister must preach the text according to the grammatical-historical-theological method.

The grammatical element would deal with the nouns, verbs, tenses, cases and all other pertinent exegetical aspects (i.e. syntax, use of idioms, metaphors, etc.).

The historical element would include understanding the authors context, audience, and the overall purpose of the book as a whole. Was a particular book written as an evangelistic tract to a particular group? This seems to have been true of the Gospel of Matthew. Is it a polemic against some particular error jeopardizing the Gospel? Such was the case with the letter to the Galatians. Was it written to deal with a particular deficiency in the life of the church? The epistle of James is an example of such a letter. Was it written to show forth the missional nature of the church in the world? This was certainly the case with the book of Acts. There are many helpful Old and New Testament Introductions available to ministers to help them navigate through the more challenging historical settings. For instance, this is helpful for the historical aspects of the Old Testament, and this for those of the New Testament.

The theological element of our interpretation would include the redemptive-historical (canonical) setting and the systematic-theological categories of Scripture. This means that we need to have a good grasp on the organic unity of the Scriptures. We need to understand how all of the Scriptures are organically related to God’s promise of redemption in Genesis 3:15 and that all of Scripture is eschatological (i.e. moving toward a consummated goal through the finished work of Jesus). Vern Poythress’ article, “The Presence of God Qualifying Our Notions of Grammatical-Historical Interpretation: Genesis 3:15 as a Test Case” is one of the most helpful treatments of the “theological” element in our biblical interpretation. If we leave any of the three elements of interpretation we do ourselves and our listeners a great diservice. Many who seek to “make the Scriptures” relevant to their hearers are guilty of leaving off one or another of these; but many in solidly Reformed churches are often also guilty of over-emphasizing one or another in their preaching. More will be said about these categories throughout this post.

Textual Context

I had a professor in seminary who used to say, “Just as the three rules of realty are ‘location, location, location,’ so it is with preaching. The three rules of preaching are ‘context, context, context.” Textual preaching is simply the faithful contextual preaching of a passage of Scripture as defined by a particular self-contained pericope. You might choose to divide a text into a larger or smaller section. The divisions found in most English Bibles are, in many cases, the most naturally manageable divisions to preach. You do need to be careful, however, not to divide it simply because the English translators have given you division headings in your Bible. Sometimes the translators fail to include a verse or two before the break or a verse or two after the break that would naturally go with the exegetical flow of the writer’s argument This is where knowing the flow of the book as a whole is the only way to properly contain the pericope. The professor I mentioned above would encouraged the students to print out, in Hebrew or Greek, whatever book we would preach through and then to remove chapter divisions and verse numbers. This way the minister learns to do his own dividing of the text and is forced to think through where a natural division might be in a more informed manner. For instance, If you wanted to preach through the book of Romans you would, at some point, divide the book into naturally divided passages. You would want to look for Paul’s line of argumentation, consider how much you are able to preach in a 30 min. period and so divide the book into manageable, naturally divided texts. If you came to Romans 5, you might divide it into three sections: Romans 5:1-5, Romans 5:6-11 and Romans 5:12-21.

The goal with all textual preaching is to drain everything in the text out of the text. This means that we need to labor to stay close to the text. It’s never good to stray far from the text. Many ministers use a text as a springboard from which to jump off into a particular topic they wish to talk about or into another related passage of Scripture. Textual preaching does not do this. Textual preaching seeks to hold forth the proposition of the pericope and to exposit the main point of the text from the text itself. At first this will feel restrictive to the preacher. It is far easier to jump around. But the Holy Spirit has inspired each passage of Scripture–ordering all the words and arguments in the way in which they are written by the human authors. The more men seek to preach textually the easier the other contexts become to discern.

Textual preaching must connect the passage you are preaching with the context of the chapter, or wider context, in which it is found. In my totally biased opinion, no one does this as well as Sinclair Ferguson. Especially when he is preaching a passage in the Gospels, Ferguson connects the more narrow context of what went immediately before or what comes immediately after the text from which he is preaching. In his sermon on Matthew 11:25-30, “The Greatest Rest You’ll Ever Enjoy,” Ferguson ties Jesus’ words in Matthew 11:28-29 to the context of Matthew 12:1-14. When Jesus says, “Come to Me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take My yoke upon you and learn from Me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls” this can only be fully appreciated when it is seen against the background the subsequent accounts mentioned in Matthew 12:1-14. Since there were no chapters divisions given by inspiration of the Spirit, Ferguson models how to read the text in its immediate context. In this way, the words of Jesus find fuller significance as we see them in the context of the theological purpose of the Sabbath day–the day of redemptive rest. I have had many “Ah ha!” moments while listening to Ferguson preach a text in its immediate context–which I had missed so often. This is what we meant by textual context.

Expositional Context

The title “expositional” may be a bit misleading since we’ve already said that “expository” preaching is the book-by-book, text-by-text preaching of Scripture. Anyone who preaches through a book of the Bible passage-by-passage can claim to preach expositionally. However, when we speak of “expository” here we are referring to the wider context in which the immediate textual context (i.e. preaching portion) is positioned. This is the context of the book as a whole. In this sense, expository preaching is that which reminds the hearers of the relationship between the text you are preaching and the context of the book as a whole. Martyn Lloyd-Jones was actually quite skillful at reminding his hearers of the argument of the book and the relationship that the passage or verse he was preaching held to what had gone before. The preacher may also tie in what is coming in the book at certain points in his exposition of a text–provided that there is a clear and unmistakeable connection between what he references from later in the book and that which he is currently dealing with. It takes great skill to know what to incorporate from other portions of the book from which you are preaching, and what to leave out of the message you are currently preaching. There is always the danger of dancing around too much in the book from which you are preaching. Staying close to the text will solve this problem for most. John Piper’s sermon series on the book of Romans is a fine example of textual preaching that always draws from the wider context of the book of Romans as a whole.

Redemptive-Historical Context

While we have already briefly touched on this under the explanation of the theological element of our hermeneutic it will be helpful for us to consider the broadest context in which every text finds it’s placement. In recent years “Christ-centered” preaching has undergone something of a surge in Calvinistic and Reformed churches. What is meant by the phrases “Christ-centered” and “Gospel-centered” is not always clear. It may do us better to speak of the redemptive-historical context of preaching. The Bible is one story–a metanarrative about the redemptive plan of God–in which every part is organically related and finds its fulfillment in the Person and work of the Lord Jesus Christ. Time would fail us to deal with this subject in any depth here, but it will suffice to say that every text of Scripture finds a place in the context of redemptive-history. Jesus said, “Moses wrote of Me,” and “Abraham saw My day,’ and “Without Me you can do nothing.” The Apostle Paul said, “God forbid that I should boast except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ,” and ‘We do not preach ourselves but Christ Jesus the Lord,” and “I determined not to know anything among you except Jesus Christ and Him crucified,” and “just as long as Christ is preached,” and “that in all things He should get the preeminence,” and “Him we proclaim,” and “All the promises of God are ‘Yes’ and ‘Amen’ in Him.” These are only a few of the more prominent verses that are used to defend the teaching that all the Scriptures center on Christ and the work of redemption. In other words, there is no promise, no warning and no teaching, no exhortation that are not founded on the finished work of Jesus. A while back I wrote a post titled, “How Redemptive-History and Example Meet in the Book of Hebrews” in order to explain how the warnings of the book of Hebrews are never separated from the Gospel promises. I have also written several biblical-theological posts to help guide others into a consistently Christ-centered approach to reading the Bible. After all, Jesus did this very thing when He opened the Scriptures to the two on the road to Emmaus and taught them all things about Himself out of the Law and the Psalms and the Prophets (Luke 24).

We need to learn to preach Christ out of the Old Testament, out of the Gospel narratives, in the Epistles and in Apocalyptic literature . None of these things are easy. All of them take the illuminating work of the Holy Spirit together with a strong grasp of Scripture. The men who do this best are those who develop over time what my friend Stephen Burch calls “a Gospel fluency.” The book that covers all of these areas best is Dennis Johnson’s Him We Proclaim.

As far as preaching Christ in the Old Testament is concerned, Sinclair Ferguson’s Proclamation Trust pamphlet on the subject is an unparalleled resource. In addition Edmund Clowney’s books The Unfolding Mystery and Preaching Christ in All of Scripture are exceedingly helpful. In the history of the church, one of the richest treatments of redemptive-history is found in the opening chapters of Jonathan Edwards’ A History of the Work of Redemption. There are so many other biblical-theological and redemptive-historical books and articles that one could fill up a lifetime of study on this subject.

There is significantly less written to help ministers preach Christ from the Gospels. That may sound like a superfluous way of talking about the Gospels. After all, aren’t the Gospels about Jesus? Actually preaching Christ in a redemptive-historical manner is more challenging than many have acknowledged. It is too easy to preach a text atomistically. In other words, it is actually possible to preach a portion of the Gospels (e.g. some part of the Sermon on the Mount) and miss the Savior who is heading to the cross to make all of His teaching powerfully effective in the lives of His redeemed and forgiven people. I’ve tried to deal with this subject in some detail in “The Sermon on the Mount and the Savior on the Mount,” “The Parable of the Three Lost Sons” and “Reading the Gospels in Light of the Gospel.”

Because of the clear didactic nature of the epistles there are still far fewer resources available on preaching Christ in the epistles. I would recommend Joseph Pipa’s two lectures from the 2005 Banner of Truth Conference on “Preaching Christ in the Epistles.” Additionally, Geerhardus Vos once explained why it is easier to preach Christ and redemption out of the epistles than from the Gospel narratives when he wrote:

“The relation between Jesus and the Apostolate is in general that between the fact to be interpreted and the subsequent interpretation of the fact.”

The Gospels give us the history of Jesus and the epistles give us the inspired interpretation of that history. Nevertheless, we still need to avoid the danger of atomistically preaching a text in the epistles, or to so preach the imperatives at the end of all the Pauline epistles apart from the indicatives of Christianity upon which they rest. The expository context helps preserve the redemptive-historical context in many cases because the beginning of most of the epistles starts by pointing us to Christ, His saving work and benefits. If we remember that Christianity is founded on the indicatives of what God has done for us in Christ we will avoid taking up the imperatives that follow in a legal or guilt-driven manner. So much more could be said about the importance of the redemptive-historical context, but the more we saturate ourselves in the truths of the Gospel the more we will develop a “Gospel-fluency.”

A few cautions should be raised at this point. It would be a mistake to only preach Christ to the exclusion of preaching the Father and the Spirit. Our preaching must be Theo-centric, Pater-centric and Pneuma-centric as much as it is Christo-centric. The difference lies in the fact that only the Son is the mediator between God and man. This makes Him the central figure of the Godhead in our preaching. Another caution would have to do with the possibility of turning a redemptive-historical element of hermeneutics into the totality of our homiletic. This is the chief criticism often raised against the extreme versions of “Redemptive-Historical Preaching.” A hermeneutical principle can never take the sole place in a homiletical method. This danger can occur with systematic theology as well. We have to integrate the redemptive-historical elements into the sermon as they are naturally highlighted in the immediate context of the text. This is not always an easy task. We have to give ourselves to a diligent study of the text and meditation on it’s relationship to Gen. 3:15 and redemption.

Applicatory Context

A friend of mine once said that the Proverbs were like an echo board in which the truths of Scripture echo out into the world and into the lives of all men and women. This helped me understand how the broadest context in which the text of Scripture functions is the context of our own lives. Preaching that has no application is inept preaching. Even though I would argue that the power for experiential living comes from the Gospel and the accurate exposition of Scripture, experiential application pinpoints that power to the different areas of our lives. Most Christians are not skilled enough to take the theology of Scripture and apply it to themselves. They need the minister to give them the “cash value” of whatever is being preached. The applications of a particular text are seemingly unlimited because there are so many areas of our lives in which we need to experience the truths of Scripture.

A caution must be raised at this point about the proper way to apply a text. It is actually quite possible to misapply a text because of zeal for some particular doctrine or practice. For instance, Sinclair Ferguson’s exposition of Matthew 11:28-29 is a good example of how to faithfully apply a text. An inappropriate application of Matthew 11:25-12:12 would be an extended exhortation to Sabbath observance. While there is everything right in having sermons that apply the fourth commandment to the lives of believers, the purpose of Matthew 11:25-12:12 is not to make people zealous for public and private worship practices on the Lord’s Day. The point of that passage is to focus on the One who fulfills the Sabbath rest for us and who is Himself able to give rest to the souls of men and women. Surely one could apply Matthew 12:7 and 12:12 to the lives of believers in a way that presses their calling to be merciful and do good on the Lord’s Day, but this is not the overarching focus of Matthew 12:1-12. If we miss the redemptive-historical context of the text we would almost have to resort to those sort of applications as the central application of the text; but when we come to understand the canonical setting we see that it is focused on Jesus and His saving work for us that is in view. The applications would then be focused more on our need for Christ and an understanding of what He is like rather than on what we should do on the New Covenant Sabbath.

We also must labor to know our congregants in order to know how to better apply the text to them. Every congregation is different and has different needs (as is evident from the different content of the epistles and the way Jesus addresses the seven churches in Revelation 2-3). This takes intentionality as a pastor. We must be sensitive to where are hearers are. We must approach this with a desire for “discriminating” application. Some of our hearers will be believers; some unbelievers; some adults; some children; some will be putting sin to death in their daily walk; some (usually most) will be loosing battles with sin; some of your hearers will be hypocrites; some will be wounded believers; some need encouragement; some reproof. This is one of the more difficult challenges in preaching. Know the condition of the flock and know what they need to hear. One one hand, you can say that they need to hear whatever Scripture says; on the other, you must understand that they need specific and natural applications of the text to their respective daily experiences.

Perhaps the most helpful book on application in preaching is John Carrick’s The Imperative of Preaching. While I don’t agree with all of Carrick’s criticisms of the redemptive-historical school, I do agree with his assessment of our need to know how to apply imperatives and applications in our preaching.

As has been noted already in this post, it would be impossible to deal in any sort of comprehensive way with the categories of “textual, expository, redemptive-historical and applicatory” preaching. I do hope that this will open avenues of thought, meditation and study as all those called to Gospel ministry labor to become the most faithful expositors of Scripture. I would also be remiss if I did not give one final charge–that is, we must subject all of our study and preparation to prayer. Everything we do in sermon prep must be bathed in prayer. We must call down the divine blessing on our preaching because we are merely earthen vessels from which the Gospel is proclaimed and the Kingdom of God carried forward. We are all insufficient and weak; we will all fail in many ways. Nevertheless, the pressing need of our generation–as has been true of all preceding generations–is for God to raise up passionate, Scripture-saturated, theologically strong, godly, and biblically faithful men to proclaim the Word of God. May God bless our feeble efforts to His glory and honor, and may the cry of our hearts always be that the Lord Jesus would increase in our preaching and that we would decrease.

Any reason why you recommend Machen’s NT Intro over Carson and Moo’s? And similarly for Hendriksen’s survey rather than Longman and Dillard’s OT Intro, or EJ Young’s?

David,

I did consider giving a list of other Intros but these are the two from which I have benefited most. I think that they are both extremely underrated unlike those by Carson/Moo and Dillard/Longman. I also think that there is a covenantal approach to Machen and Hendriksen that you don’t get in Carson/Moo and that Dillard/Longman sort of tamper with. There is far too much dependence on ANE and adaptation of higher critical principles in Dillard/Longman. Young’s work is phenomenal. I thought about recommending it, but I find that the outlines in Hendriksen’s volume are a bit more useful than what you find in Young. I do think we should read as many Intro’s as possible. There are many other good ones out there.

Thanks Nick, that’s extremely helpful. I have Carson/Moo and Hendriksen but have been considering getting the other three as well.

“There is far too much dependence on ANE and adaptation of higher critical principles in Dillard/Longman.”

What is “ANE”?

Ancient Near Eastern literature.

Nick, this is a well-balanced article. I’m afraid that both sides of the RH divide have polarized each other and lost much of the benefit of each others’ positions. The point about one aspect of exegesis taking precedence over others – ST, BT or RH model is well made. They are all tools available to the minister, and all need to utilized.

Nephelies gen ch 6 who are they