The “Not I, but the Lord…I say, Not the Lord” Sayings of Paul

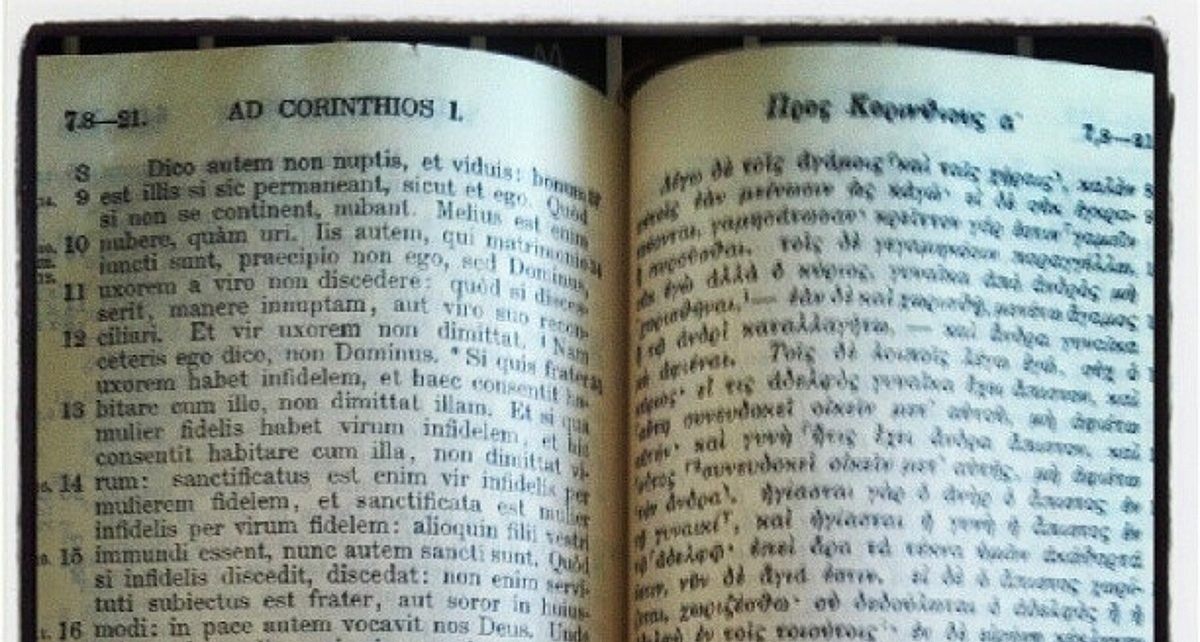

John Murray, Professor of Systematic Theology at Westminister Theological Seminary in Philadelphia from 1930-1966, wrote what I believe to be the single most helpful chapter on the internal testimony of Scripture. In “The Attestation of Scripture,” in the Westminster Seminary faculty symposium volume The Infallible Word, Murray handles objections raised against the idea of Divine inspiration and apostolic authority on account of the language used in such places as 1 Corinthians 7:10-12 and 1 Corinthians 14:37-38. In 1 Cor. 7:10-12 Paul employs phraseology that might be construed as unauthoritative judgment when he wrote, “Now to the married I command, yet not I but the Lord: A wife is not to depart from her husband. But even if she does depart, let her remain unmarried or be reconciled to her husband. And a husband is not to divorce his wife. But to the rest I, not the Lord, say: If any brother has a wife who does not believe, and she is willing to live with him, let him not divorce her.” Does this mean that part of our Bible is not authoritatively binding–that these passages are just pious advice? Seeking to set out an accurate explanation of what Paul actual meant, Murray wrote:

The passage in I Corinthians 7:10-12 is sometimes understood as if Paul were instituting a contrast between the authoritative teaching of Christ and his own unauthoritative judgment on questions bearing upon marriage and separation- “But to the married I give charge, not I but the Lord. …But to the rest I say, not the Lord.” A careful reading of the whole passage will, however, show that the contrast is not between the inspired teaching of Christ and the uninspired teaching of the apostle but rather between the teaching of the apostle that could appeal to the express utterances of Christ in the days of his flesh, on the one hand, and the teaching of the apostle that went beyond the cases dealt with by Christ, on the other. There is no distinction as regards the binding character of the teaching in these respective cases. The language and terms the apostle uses in the second case are just as emphatic and mandatory as in the first case. And this passage, so far from diminishing the character of apostolic authority, only enhances our estimate of that authority. If Paul can be as mandatory in his terms when he is dealing with questions on which, by his own admission, he cannot appeal for support to the express teaching of Christ, does not this fact serve to impress upon us how profound was Paul’s consciousness that he was writing by divine authority, when his own teaching was as mandatory in its terms as was his reiteration of the teaching of the Lord himself? Nothing else than the consciousness of enunciating divinely authoritative law would warrant the terseness and decisiveness of the statement by which he prevents all gainsaying, “And so ordain I in all the churches” (1 Cor. 7:17).

That Paul regards his written word as invested with divine sanction and authority is placed beyond all question in this same epistle (1 Cor. 14:37,38). In the context he is dealing specifically with the question of the place of women in the public assemblies of worship. He enjoins silence upon women in the church by appeal to the universal custom of the churches of Christ and by appeal to the law of the Old Testament. It is then that he makes appeal to the divine content of his prescriptions. “If any man thinketh himself to be a prophet or spiritual, let him acknowledge that the things I write unto you are the commandment of the Lord. And if any man be ignorant, let him be ignorant.” Paul here makes the most direct claim to be writing the divine Word and coordinates this appeal to divine authority with appeal to the already existing Scripture of the Old Testament.

In the earlier part of this epistle Paul informs us, in fashion thoroughly consonant with the uniform teaching of Scripture as to what constitutes the word of man the Word of God, that the Holy Spirit is the source of all the wisdom taught by the apostles. “God hath revealed them unto us through the Spirit. For the Spirit searcheth all things, yea, the deep things of God” (1 Cor. 2: 10). And not only does Paul appeal here to the Holy Spirit as the source of the wisdom conveyed through his message but also to the Spirit as the source of the very media of expression. For Paul continues, “which things also we speak, not in the words which man’s wisdom teacheth, but which the Spirit teacheth, combining spiritual things with spiritual” (1 Cor. 2:13). Spirit-taught things and Spirit-taught words! Nothing else provides us with an explanation of apostolic authority.

Much else that supports and corroborates the foregoing position could be elicited from the witness of the New Testament. But in the brief limits of the space available enough has been given to indicate that the same plenary inspiration which the New Testament uniformly predicates of the Old is the kind of inspiration that renders the New Testament itself the Word of God.