The Unimportance of what God’s People Think About Him

I am sure that all of us have heard many professing Christians say something like, “I like to think of God as being like this or that…” or “I don’t think God would do this or that…” In his article The God of Israel, B.B. Warfield, explained the significance of the fact that in both the Old and the New Testament we find an absence of statements about what the covenant people thought God was like; rather, we find what the people of God should be thinking about Him as He reveals it to them in his inspired word. While it is certainly important what the human authors of Scripture thought of God as He revealed Himself to them by inspiration of the Spirit, it was not a private interpretation (2 Peter 1:20). This has profound implications for us today in our use of such things as Ancient Near Eastern Literature and the literature of Second Temple Judaism. It is not primarily what this individual, or that individual, or this group of people, or that group of people thought about God; instead, it is principally about what God has revealed Himself to be in His word. Warfield developed this idea along the follow lines:

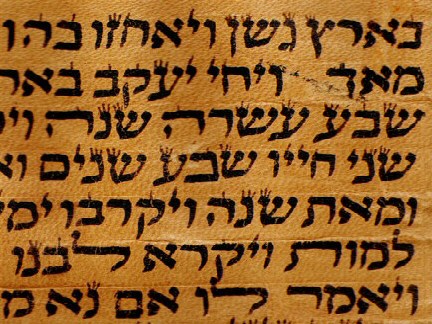

The Old Testament does not occupy itself with how Israel thought of God. Its concern is with how Israel ought to think of God. To it, the existence of God is not an open question; nor His nature; no accessibility of knowledge of Him. God Himself has taken care of that. He has made Himself known to His people…the fundamental note of the Old Testament, in other words, is Revelation. Its seers and prophets are not men of philosophic minds who have risen from the seen o the unseen, and, by dint of much reflection, have gradually attained to elevated conceptions of Him who is the author of all that is.1

He then drew out the argument by way of comparison:

Similarly today, a curious inquirer might doubtless uncover some very odd, some very gross, some very wicked notions about God, lurking in the minds of these or those Christians. But as it would be unfair to look upon these strange, perhaps unworthy notions of God as the God of Christianity, merely because they have been or are entertained by some Christians, so it would be unfair to think of those inadequate or debasing ideas of God which some Israelites betray clinging to their minds, as the God of Israel. The Christian God is not the God which some Christians have imagined for themselves; not even the God which all true Christians believe in; nor even the God who the best of Christians intelligently worship…the Christian God is the God of the Christian revelation. And the God of Israel is not the God which some Israelites have fancied to be altogether like unto themselves, or, perhaps, something infinitely less to be admired than themselves: but the God of the Israelitish revelation. He must be sought, therefore, not in the thought of Israel, but in His own self-disclosure through His prophets.2

1. B.B. Warfield Selected Shorter Writings (Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R Publishing, 1970) p. 82

2. Ibid., p. 83

Excellent.

In the same vein, I was helped by Owen’s distinction between the development of theology by revelation in redemptive history and the subsequent defections from that theology among its recipients. The Scripture certainliy records those defections, but they must be viewed as such against the backdrop of the “faith once received.”